Terryl Givens on Mormon Universalism

Posted on Dec 3, 2011 by Trevor in Religion

The following is a partial transcript I made of an excellent Mormon Stories podcast interview with Terryl Givens, one of the most intellectually interesting and thoughtful Mormons I know of. His strong literary background and thoughtful nature provide him a unique perspective and ability to express himself. This transcript comes from part 2 of the podcast, 37:30 – 39:20, and part 3, 10:30 – 29:15. Givens lays out the case for Mormon universalism, or how a minority religion often viewed as exclusionist and triumphalist actually contains the elements for salvation for the entirety of the human race as opposed to just God’s favored people.

The following is a partial transcript I made of an excellent Mormon Stories podcast interview with Terryl Givens, one of the most intellectually interesting and thoughtful Mormons I know of. His strong literary background and thoughtful nature provide him a unique perspective and ability to express himself. This transcript comes from part 2 of the podcast, 37:30 – 39:20, and part 3, 10:30 – 29:15. Givens lays out the case for Mormon universalism, or how a minority religion often viewed as exclusionist and triumphalist actually contains the elements for salvation for the entirety of the human race as opposed to just God’s favored people.

Terryl Givens: Here’s the other remarkable thing about Mormonism, and it saddens me that Mormons haven’t caught hold of the power and the beauty of this aspect of their theology. You know, Mormons, ironically (this is just perversely ironic), Mormons are criticized for being exclusionist, right? We shut down the temple to all except those who have recommends, and we talk [about how] you gotta be a Mormon… No! Mormons are the most inclusivist theological system that exists in the Christian world, separate and apart from Universalist Unitarians themselves. In Joseph’s Smith’s vision, everybody is going to be saved, except that handful who absolutely refuse to accept the conditions of their salvation.

And it strikes me that this is the greatest selling point, so-to-speak, of Mormonism, is a God who says, as we’re told [in] D&C 88, that beautiful verse where we’re told that everybody will receive that which they are willing to receive. So, you know, all the universalists in Joseph’s day were writing about this. They were saying, “Yeah, it just doesn’t make sense that God would condemn you if you’re not baptized, or you were born a pagan.” But they didn’t know how to reconcile the need for a Savior with that desire to universalize salvation, and Joseph comes along and reveals this whole plan of vicarious salvation, work for the dead, teaching the Gospel in the Spirit World. I mean, God is not only the most compassionate, but He’s the most generous and inclusive God of any creedal system. It’s just marvelous to me.

And it strikes me that this is the greatest selling point, so-to-speak, of Mormonism, is a God who says, as we’re told [in] D&C 88, that beautiful verse where we’re told that everybody will receive that which they are willing to receive. So, you know, all the universalists in Joseph’s day were writing about this. They were saying, “Yeah, it just doesn’t make sense that God would condemn you if you’re not baptized, or you were born a pagan.” But they didn’t know how to reconcile the need for a Savior with that desire to universalize salvation, and Joseph comes along and reveals this whole plan of vicarious salvation, work for the dead, teaching the Gospel in the Spirit World. I mean, God is not only the most compassionate, but He’s the most generous and inclusive God of any creedal system. It’s just marvelous to me.

In part 3, the interview has taken an interesting tone, where John Dehlin, the interviewer, is almost using Terryl as his own personal belief consultant. John queries Terryl in general about the traditional Mormon concept of the Great Apostasy following Jesus’s ministry, and the seemingly tribal God found in the scriptures that only interacts with His small group of chosen people, be they Nephites or Israelites, to the exclusion of the vast majority of humanity outside these privileged groups. Is it not terribly inefficient, John asks, that God’s divinely sanctioned religion has such a limited reach? “It’s so narrow,” he laments, “and so few of God’s children are privileged to actually benefit from the teachings.”

Terryl Givens: Well, I think about it largely through the prism of, again, my wife Fiona, who was raised a Catholic, and brought to her Mormonism a wonderful set of perspectives and understandings. She was the one who first pointed out to me that, if you look at the allegory of the woman in the wilderness, in chapter 12 of Revelation, that Joseph glossed that in a particular way, or he says, “That’s about the apostasy,” right? And then the woman flees into the wilderness?

Well, what I find absolutely remarkable is that when Joseph recorded the very very first revelation that mentions the Church that he’s going to restore, at first he talks about the formation of a Church in the Book of Commandments. But when he recasts that revelation in Doctrine and Covenants 5, he changes the wording, and he refers to the coming forth out of the wilderness of the Church. So, he’s obviously influenced by Revelation 12. He’s inspired by that language and he’s trying to draw a parallel. And what Revelation 12 says is that the truth was not taken from the Earth, but that it retreated into the wilderness where it was nurtured of the Lord.

Now think about the implications of that. The Church is in the wilderness; it’s being nurtured by the Spirit of the Lord, throughout this period of so-called darkness and apostasy. This, to my mind, gives us a radically different paradigm for understanding the relationship of Mormonism to the rest of the Church and understanding the place of Mormonism in dispensational history. It also gives us an answer to the question, “When is Mormonism going to produce a Dante, or a Shakespeare, or a Beethoven?” And the answer is, “We don’t need a Mormon Dante, or Shakespeare, or Beethoven. We have Dante, and Shakespeare, and Beethoven. We’ve got Handel’s Messiah. Why do they have to be authored by Mormons?” In other words, Joseph seemed to be suggesting that there is this reservoir of truth and beauty throughout the Christian world and even beyond, and his job was to try to select from these scattered fragments of Mormonism and reconstitute them into an institutional church.

But the point is God has made abundant provision for there to be sources of inspiration, truth, and beauty throughout culture and throughout history. Mormons don’t have the monopoly. And, in the book When Souls Had Wings, I engaged in an experiment upon that principle, where I investigated the history of one such idea, the Pre-existence, and found that, indeed, there are hundreds and hundreds of manifestations of that beautiful truth in history, philosophy, theology, and art, throughout the West, going all the way back to earliest recorded religious history. So that’s the first point that I would make, is that this so-called “narrowness of Mormonism” isn’t the problem that we think it is, because nobody is claiming (or nobody should be claiming) a Mormon monopoly on the avenues to these truths and what they represent.

Second of all, I think if I go back to my statement about the most important part of the institutional Church being the ordinances of the temple, then you don’t need a church of two billion people, if your principle role is to serve as custodian of those rituals and make them available, and also provide the means whereby their benefits can be extended to the entire human family, either vicariously now, or throughout the Millennium, or however you expect that’s going to be fulfilled.

And then finally, if you return to what I said earlier about Mormon universalism, then you understand that you don’t have to be a member of the institutional Church in order to secure your salvation. So, I think the image is much more apt, to think of Mormonism in the way that Christ referred to the leaven and the bread: all it takes is a little bit of leaven. And Mormonism is here to provide that, as I understand it.

John appreciates those sentiments as being “beautiful”, but counters they appear to be out of place compared with longstanding rhetoric in the LDS Church. “But that’s not how we’ve culturally evolved, with the encouragement and seeming endorsement of our top leadership,” John explains. He feels the Mormonism he was raised with taught him  “to feel sorry for everyone around me that wasn’t Mormon, to consider them to be less-than, to consider our Church to be superior in every way. And I didn’t even feel like I was raised with any type of encouragement to feel reverence or respect [towards other faiths].” John then mentions in mock tone a few traditions of other religions that he learned about under the context of ridicule. He then continues, “If we mentioned any other religious tradition at all, it was to compare how wrong they were and how right we were.”

“to feel sorry for everyone around me that wasn’t Mormon, to consider them to be less-than, to consider our Church to be superior in every way. And I didn’t even feel like I was raised with any type of encouragement to feel reverence or respect [towards other faiths].” John then mentions in mock tone a few traditions of other religions that he learned about under the context of ridicule. He then continues, “If we mentioned any other religious tradition at all, it was to compare how wrong they were and how right we were.”

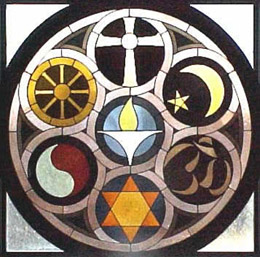

Conceding that this triumphalist mindset isn’t limited only to Mormons, John explains that it nonetheless set him up for a religious “PTSD” or faith crisis, as it led him to “acquire a world view that I was better than everybody.” This could leads to people’s faith being shattered, he exasperates, because they could get reared under such a mindset in the Mormon Corridor (i.e. the geographical area running from Idaho to northern Arizona where the population is heavily Mormon), and then go out into the world and “they find these amazingly, wonderful, thoughtful, spiritual Jews, or Catholics, or Muslims, or Hindus, or Buddhists, or atheists.” They then feel terribly deceived about humanity. John asks, “We come by [this negative] mindset honestly, right? Or not? Was I just in this corner of Mormonism that was out of touch with this broader, expansive view that you’ve just communicated?”

Terryl Givens: No, I think what you’re describing began in the Brigham Young years. If you look at the rhetoric of Brigham Young and everyone else speaking in the Tabernacle in the 1850s and 60s, you see pretty virulent hostility and animosity towards the rest of Christiandom, and you can see that that’s the aftereffects of the martyrdom and the expulsion. And then what happens in the 20th century, of course, is the kind of diatribe against the Catholic church which pervades our culture. I think that we as a Church are guilty of an institutional sin in the way that we have trumpeted Mormon triumphalism at the expense of the virtue and value of other religious traditions and individuals, and that’s a sin for which we need to collectively repent.

But I would say that there’s nothing conducive, well, not nothing… There isn’t [laughs] a lot that’s conducive to such a view in Joseph Smith himself. Now, many people point, rather unfairly I think, to the language of the First Vision experience where he talks about [how] the [creeds of other religions] were an abomination, you know. But give me a break. He’s writing in a 19th century vernacular in which that kind of language is absolutely de rigeur.

John Dehlin: What do you mean? Wait. Translate. Because it is offensive to me. D&C 1 is offensive to me. But I know people who don’t see it that way. So how can I not see it that way?

Terryl Givens: Because you can’t find any religious language in the early 19th century that isn’t exclusivist in that way, that isn’t triumphalist, right? [partly joking] The Baptists hate the Catholics. The Catholics—I mean, for heaven sakes, right?—the Catholics are the Great and Abominable Church of the Devil to everybody. I mean, that’s not unique to the Book of Mormon. And they couldn’t hold office in half the states before the Civil War. Just read any of the pamphlet wars going on in the early 19th century, and the rhetoric is just absolutely beyond the pale. So Joseph Smith is simple employing a vernacular, as I said, that is absolutely typical of religious culture in the early 19th century. Unfortunately, it ends up being canonized in scriptures that we still read and disseminate today. And that’s part of the reason for this triumphalist rhetoric that’s been very damaging.

But my sense is things began to change under President Hinckley. Not just because he was much more media savvy and conscious, but because from the pulpit, he actually said on occasion that language of us being the “only true church” can be misunderstood, it can be hurtful, it can be harmful. And so I think he tried to encourage a retreat from that kind of language and that kind of attitude. But I think we’ve been very slow to catch on to that.

Trying to clarify or expand Terryl’s position, John searches for a metaphor that could further explain it. He suggests that perhaps the variety of religious traditions on Earth is comparable to what Elder Joseph Wirthlin described in his timely conference talk on the orchestra God is conducting, with each instrument playing an important role, and none of them holding primacy over other instruments. God needs the piccolos just as much as He needs the percussion. Is Mormonism “but one player in the symphony?”

Terryl Givens: Well, they’re one player. They’re the player that He designated, to whom He actually bestowed what I believe are very real keys of authority and responsibility. I believe also that the fullest dispensation of truth was made available through Joseph Smith. There isn’t a single other Christian denomination on the planet, for example, that espouses belief in the eternal identity of the human soul. That, to my mind, is a critical, really important component of the whole Gospel picture that’s available through the restored Gospel that we call “Mormonism”—an understanding of human potential and the capacity that we have to become fully like our Father in every way. That’s unique to us. There’s an array of Gospel teachings. It’s not that we have to know all of these things in order to become God-like people. But I think the more fullness of the Gospel we are able to imbibe and have access to, then the greater will be our ability to make progress across the whole array of areas where we need to progress toward a God-like nature.

So, no, I think there is a qualitative distinction. What I’m saying is the fact that we have a particular mandate and a particular responsibility as custodians of the Priesthood and the temple ordinances doesn’t mean that there aren’t other important players in this cosmic drama as well, and much that we can learn.

Still trying to ensure he’s on the same page, John expands the music metaphor. Perhaps Mormonism’s role in the orchestra is comparable to that of percussion, providing the tempo, beat, and rhythm that everyone else integrates with and upon which they base their performance. “It’s unique, and it’s different, and it’s special, and it’s critical. … But the other pieces also are critical, and maybe even the other pieces have their own sanctioned authority in God’s mind and planning, and even crucial parts to the overall plan and destiny of humanity. Can you grant that, too?”

Terryl Givens: I don’t see why not. I think [with respect to] the very designation “Mormonism”, I understand to a great degree why the brethren don’t like the use of that term. I use it because it has a certain valence and cultural history that “LDS” doesn’t. But the danger is to assume that Mormonism has an eternal status, and it doesn’t. Mormonism is the particular incarnation of the Church of Jesus Christ at this moment in time. Everybody will eventually have to bow the knee and confess that Jesus is the Christ. But everybody doesn’t have to be a Mormon and everybody doesn’t have to be LDS. But right now, that Church offers a pretty effective vehicle to get to know Christ and comply with his ordinances.

John Dehlin: Right. So substitute what I said about Mormonism to the LDS Church as an institution, and all I’m trying to say is [that] I have to find a way to piece together a theology, if I’m going to keep believing, that looks with respect and love to other beliefs and non-beliefs, that doesn’t place us in any way higher than them, but instead says, yes, we stand up and say we have an important role to play in the Plan of Salvation. An essential role. But we also realize with humility that there are other essential roles, and somehow it aggregates into something very universalistic and beautiful that is respecting of all traditions and even inclusive of them, not denigrating and relegating. Does that make sense?

Terryl Givens: Yeah, well that’s not just your opinion. That’s what the Lord was saying in 1831 when He said to Joseph, “There are other holy men that I recognize that are engaged in my work that you don’t know anything about.” [Note, see also: Ezra Taft Benson – Civic Standard for the Faithful Saints, or Orson F. Whitney – Conference Report 1928, or this publication instructing church educators how to address the “one true church” concept tactfully]

John Dehlin: Hmm. And you’re saying there’s a reading of Doctrine and Covenants Section 1 and of Joseph’s vision that can still hold that respect and reverence for others?

Terryl Givens: Absolutely, if you make allowance for the historical context and the cultural conditioning out of which that language arose. And that’s why Joseph is so self-conscious about the inadequacy of his verbal presentation of these revelations. It’s not like you have to be unfaithful to Joseph or the principle of revelation to interpret that more generously. Joseph gives you that; [he] grants you that allowance when he says, “I’m struggling. This a broken, shattered language. I’m trying to do the best I can.” But his lifelong project was to revise and revise and try to more closely approximate what the Lord intended there.

John agrees, reflecting on his own understanding that Joseph was “expansive, inclusive, loving and respecting of other traditions and people”.

Terryl Givens: Absolutely. And he’s asked in Washington in 1840 in a public address he gives, “Do you have to be Mormon to be saved?” And he says, “No.”

Susan

Mar 16th, 2012

I love Terryl Givens’ thoughts on Mormonism! Thank you for the link to the Woodland Institute for the quote, “Do you have to be Mormon to be saved?” And he [JS] says, “No.” I was afraid I would not be able to find it.

I think the part Terryl Givens was referring to is as follows: “He [JS] closed by referring to the Mormon Bible, which he said, contained nothing inconsistent or conflicting with the Christian Bible, and he again repeated that all who would follow the precepts of the Bible, whether Mormon or not, would assuredly be saved.”

Interesting. I wonder if JS meant to say that “as far as the Bible is in harmony with the principles of the restored gospel (faith, repentance, baptism [by one having authority], receiving the gift of the holy ghost) then one is saved”? Otherwise, priesthood authority would not be necessary for baptism to be valid. And what about all the temple ordinances available only through the Mormon church that are not in the Bible? It would seem JS is saying they are not necessary to salvation, but the modern church says they are. I wish I understood better what JS meant here.

Trevor

Mar 16th, 2012

Well, the first temple rites were administered by Joseph Smith around 1842, which was two years after he made that statement. And the Book of Mormon is silent on temple ritual as well. So I suspect that in 1840 Joseph hadn’t even conceived of temple ordinances as being part of salvation.

Nan

Jun 20th, 2015

” And then what happens in the 20th century, of course, is the kind of diatribe against the Catholic church which pervades our culture.”

It pervades the culture because it is actively promoted through the extolling of Talmages works.

An Argument for "Mormon Universalism" - Rational Faiths | Mormon Blog

Sep 1st, 2015

[…] Terryl and Fiona Givens, for instance. More on the Givens’s approach to universalism can be found here. My strong hunch is that they would maybe even consider the term “Mormon Universalism” […]

Johnny

Jun 27th, 2016

“In Joseph’s Smith’s vision, everybody is going to be saved, except that handful who absolutely refuse to accept the conditions of their salvation.”

This loaded sentence must be analyzed thoroughly. “Damnation” in both Mormonism and other forms of theism is founded upon the nonsensical notion that one can make an unconditioned, ungrounded rejection of God.

1.) Does one imagine that those who “absolutely refuse” are not doing so based upon a particular understanding that they have? It is abundantly self-evident that there would have to be some reason for their purported refusal. If not, one would have to contend that an individual can refuse for no reason, which is obviously crossing over into unabashed nonsense.

2.) Are the “conditions for salvation” ultimately both true and good? If so, and if this is the part of a proper understanding of existence, then one not accepting of such conditions must be, quite literally, mis-understanding reality.

3.) If one’s refusal predicated upon a fundamental misunderstanding of reality, as it must if acceptance accords with a proper understanding, how can one be eternally damned for a misunderstanding? Can an individual be in full possession (or as much humanly possible) of the correct understanding of existence and subsequently make an incorrect choice (i.e., refusal)? If so, on what grounds is the incorrect choice made? Is this choice mistaken, from the perspective of one that has chosen the opposite? It must be.

4.) Can there be a mistaken understanding that cannot be rectified? If there can be, how does this occur? There must be a cause/reason for a misunderstanding. An unrectifiable misunderstanding necessitates an entirely arbitrary and uncaused rejection. Thus, conventional theism implies that one can be in possession of a truthful understanding of existence yet still make the wrong decision. Thus, they invent the existence of a phenomenon of ungrounded action; a decision that is not grounded in and devoid of any motivating factor. In short, these apologetics rely on the invented phenomenon of refusal for “no reason at all”.

Some contend that are some that will not cease from “rebelling”; that they simoly refuse the truth. This presupposes that these individuals know it is the truth and then subsequently reject it. This amounts to the claim that someone can authentically subscribe to a worldview that is other than that which seems the most truthful to them, which is pure nonsense of course. In any event, the same question arises: why did they reject it? Was it correct to reject it? However you approach it, it is incontrovertible that the incorrect choice was selected. Incorrect choices must be grounded in an incorrect perception or interpretation of reality. Furthermore, an incorrect perception of reality is not a choice any more than color-blindness is a choice.

People subscribe to an interpretation of reality fhat makes the most sense to them (i.e., seems the most truthful; the most representative of the way things are) in the context of their accumulated world experience.

In any event, the burden of proof is on those that contend that there are misunderstandings that cannot be rectified, to explain fhe dynamics of such a phenomenon. How and why do they form? Do such proponents feel that they themselves could ever be in possession of an uncorrectable misunderstanding?

Terryl Givens on Mormon Universalism | Where Mormon Doctrine Falls Apart

Jul 16th, 2017

[…] came across another article on “Mormon Universalism.” I have not listened to the interview yet, and maybe I should before I […]